The Collector of Stories: A Morning with Peterson Conway VII

- Jul 11, 2025

- 10 min read

By Jon Hite | Founder & Creative Director at HAUS of HITE

The streets of Carmel were quiet that morning, filtered through mist and the familiar hush of a town that always feels somewhere between a poem and a painting. I wandered, my mind swirling in thought, aware that I was on the precipice of something new. I hadn’t mapped out my next step with precision—I rarely do when it matters most. Instead, I let myself be guided by instinct, pulled by the silent current of energy that so often nudges us when we’re paying attention.

Five minutes later, I was standing in front of an owl. Not just any owl—an ornate carving of one mid-flight, talons stretched with calculated ferocity, frozen in a moment between stillness and strike. Above it, the words: Conway of Asia.

I’d passed this shop many times in my visits to Carmel. It had always drawn my gaze, but I’d never quite had the space—mentally or spiritually—to schedule an appointment, to really step inside and understand it. But that morning, I paused. I looked into the eyes of that owl and felt something shift. I dialed the number listed. A voicemail. I left a message. Fate set.

The next morning, I returned. The owl greeted me once more, and this time the door was open.

Inside, a Border Collie lay watch at the entrance, her black and white coat a soft welcome mat of sorts—though not without the requisite sniff of approval. After the ritual pet and tail wag, I found myself face to face with a man in a crimson shirt, phone cradled between shoulder and chin. That was my first encounter with Peterson Conway VII.

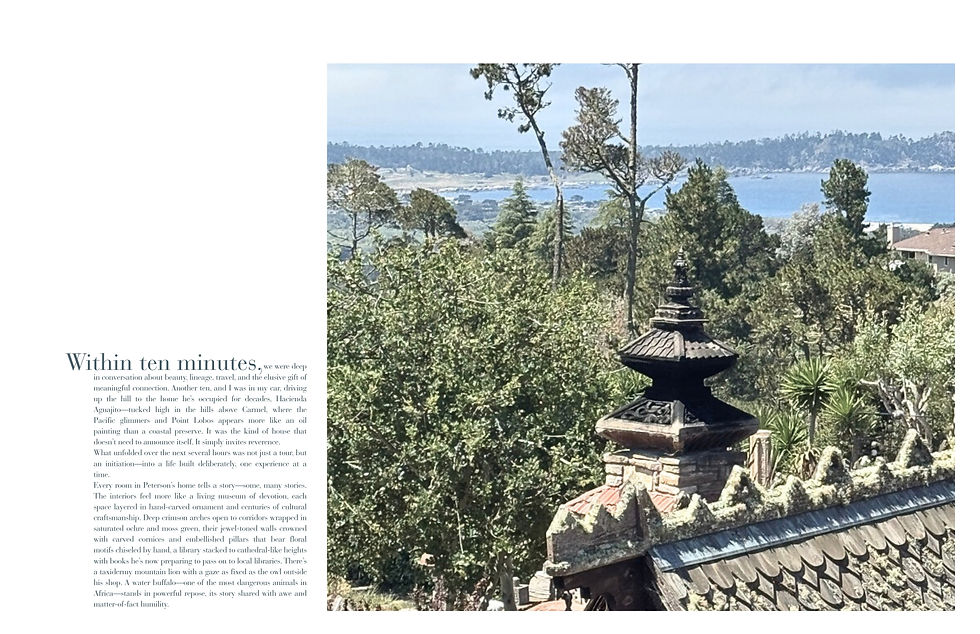

Within ten minutes, we were deep in conversation about beauty, lineage, travel, and the elusive gift of meaningful connection. Another ten, and I was in my car, driving up the hill to the home he’s occupied for decades, Hacienda Aguajito—tucked high in the hills above Carmel, where the Pacific glimmers and Point Lobos appears more like an oil painting than a coastal preserve. It was the kind of house that doesn’t need to announce itself. It simply invites reverence.

What unfolded over the next several hours was not just a tour, but an initiation—into a life built deliberately, one experience at a time.

Every room in Peterson’s home tells a story—some, many stories. The interiors feel more like a living museum of devotion, each space layered in hand-carved ornament and centuries of cultural craftsmanship. Deep crimson arches open to corridors wrapped in saturated ochre and moss green, their jewel-toned walls crowned with carved cornices and embellished pillars that bear floral motifs chiseled by hand, a library stacked to cathedral-like heights with books he’s now preparing to pass on to local libraries. There’s a taxidermy mountain lion with a gaze as fixed as the owl outside his shop. A water buffalo—one of the most dangerous animals in Africa—stands in powerful repose, its story shared with awe and matter-of-fact humility.

And then there are the details—the ones most people miss. Doorknobs that feel as though they belong in palaces. Towel racks that mirror Indian fretwork. Cornices carved with the kind of attention normally reserved for cathedrals. “No detail is too small,” Peterson said to me, almost in passing. But it landed. Nothing in his world is by accident.

There are pieces in his home with a lineage that trace directly back to the family of the Dalai Lama. Others were once part of the Taj Mahal. His Native American ancestry, through his father’s line, is honored in a sweat lodge he built himself—an ode to the traditions that shaped him from childhood, and a sanctuary of reflection in his later years.

Peterson arrived in Carmel in the 1950s, already seasoned by the world. Born into a life of privilege, he did not squander it. Instead, he devoured the globe with reverence. He swam in Parisian summer lakes. Slept atop the Bamyan Buddha, then spent the next day in a jail cell (though not for reasons you might imagine). He studied the rug trade under a blind teacher who could discern the color of thread through touch alone. He survived war zones in the Middle East, attended an impromptu feast hosted by the Shah of Iran, and once had a prized rug stolen in what would later become known locally as the “great rug heist of Carmel”—a saga that took years, thousands of miles, and a few genius minds to resolve.

These are not stories you find in books. These are stories you are lucky enough to hear in person. And I was granted the honor of hearing them first-hand. But they are not mine to tell in full. They belong to the man who lived them. If you are fortunate enough to find yourself in his presence, you’ll understand that storytelling—true storytelling—is a sacred art form.

A Gallery of Memory: Inside Conway of Asia

To step into Conway of Asia is to step into another dimension—not in a theatrical or ostentatious sense, but in a way that causes time to bend slightly at the edges. You forget what year it is. The world outside fades. You are no longer in a coastal town in Northern California—you’re somewhere in between Tibet and Marrakech, Paris and New Delhi, a caravan of stories stretching centuries.

The store is not laid out like a typical gallery. There are no sterile glass cases, no forced minimalism. Instead, every surface, every nook and corner, breathes with history. Here, a set of intricately carved altarpiece doors from Nepal. There, a collection of bronze ritual vessels used in Buddhist ceremonies. On a table rests a delicate comb made of carved bone, once used by a nomadic woman whose name has been lost to time—but whose legacy lives on through this object, now imbued with new life.

And yet, nothing here feels like a museum. There is no separation between object and observer. Everything invites touch, inquiry, reverence.

Behind the counter—sometimes sketching, sometimes cataloging, always observing—is Teresa. Elegant, thoughtful, and quietly brilliant, she is much more than a gallery manager. A trained artist, Teresa has created her own line of jewelry that reflects the ethos of the space: handcrafted from sacred stones, animal bones she’s found on long walks through Big Sur, and artifacts of forgotten eras reimagined for modern life.

She spends her time documenting the provenance of each item, ensuring that every piece carries with it the story it deserves. When you purchase something from Conway of Asia, you don’t just acquire an object—you inherit a lineage. Teresa makes sure of it. Her efforts are as much archival as they are curatorial, creating a library of stories that frees the new owner from the burden of remembering every fascinating detail, while honoring the spirit of the piece.

It’s a form of stewardship—something Peterson speaks about often, though rarely in direct terms. He believes that everything we bring into our lives should have a reason for being there. It should have weight. Energy. Meaning. This is not an ideology of minimalism, but of sacred accumulation. Of choosing what—and who—you carry with you.

And his life is the clearest example of that philosophy in practice.

The Weight of Story

Peterson Conway VII has spent his life not just collecting, but living. His home and shop are mirrors of one another—both containers for the stories he’s gathered across continents and decades.

There’s a gravity that comes with living this kind of life. It’s easy to romanticize it: the wild travel, the intimate dinners with royalty, the near-mystical stories that unravel like fables. But beneath that romance is responsibility—the kind few recognize.

Because for every great chapter lived, there must be another closed. That is the unspoken art of aging gracefully: the willingness to transition. To pass things on. To let go—not out of resignation, but to make space for what comes next.

Peterson understands this intimately. He’s done it before, many times. In his youth, it meant leaving Paris behind to venture into Africa. Later, it meant giving up the rug trade to focus on the artifacts he felt needed a new home. And now, it means preparing for another departure—this time not alone, but in the company of his grandchildren.

He talks about it openly, almost joyfully. Not with melancholy, but with a kind of reverence for the circular nature of things. “I always dreamed of taking my children around the world,” he told me, leaning against a carved teak pillar salvaged from Rajasthan. “And now, it seems the time has come… only it’s my grandchildren who are ready.”

What he is doing—what he has always done—is creating continuity. Across generations. Across cultures. Across lifetimes. His hope is not just that his grandchildren will inherit stories, but that they will learn to live them. That they will add to the tapestry, not merely observe it.

And yet, Peterson is candid in his concern. “I wonder sometimes if the next generation is ready,” he said. “Ready to hold these pieces. To carry their stories.”

It’s a question not of worthiness, but of willingness. Are we prepared to bring meaning back into our lives? Are we ready to stop treating objects as disposable and instead regard them as vessels of memory, spirit, and craft?

Peterson Conway’s world is not just rare—it is endangered. We live in a time where consumerism reigns, where fast furniture and trend-driven purchases dilute the soul of living. Objects are no longer made to last, and even less so, to be passed down. In contrast, every item in Conway of Asia carries the weight of lineage. Each has traveled farther than most people ever will. Each has been chosen. Each can speak—if you are still enough to listen.

The Sacred Transition

There’s something quietly radical about honoring the phases of a life. Not just moving through them, but honoring them—recognizing their endings, gathering their gifts, and making space for what’s next. Peterson has mastered this ritual, often without ceremony. For him, it is simply the natural rhythm of being.

That day in his home, I watched the way Peterson moved through each room—not with possessiveness, but with a curator’s grace. His relationship to his collection is not about ownership, but connection. Each item he’s acquired—whether it be the carved alabaster window from India framing a room like a sacred portal, or the painted wooden columns burnished by time and pigment—has been absorbed into the larger tapestry of his life. In one room, a photograph of an ancestor in regal dress hangs above a meticulously carved door frame, the floral latticework mirroring the delicate details of Mughal architecture. Elsewhere, a rearing wooden horse, its hooves bound in a saffron ribbon, greets visitors like a guardian of memory. Taxidermy gazelle and mountain lion watch over intricately upholstered chairs, while spiral staircases lead to libraries that stretch skyward, every shelf a testament to a lifetime of curiosity. It’s never been about things. It’s always been about what they carry.

After the tour of his home, Peterson smiled. “Go get lost,” he said, nodding toward the open hills beyond the house.

The grounds span twenty-three acres—wild, sacred, and humming with life. I wandered slowly, letting the hush of the oaks and the curve of old stone paths guide me. The land was just as ornate and intentional as the interiors of the house, echoing Peterson’s same eye for reverence and detail. There were hidden groves and carved sculptures tucked into the trees, the bones of old outbuildings reimagined into artistic relics. I could have spent several lifetimes exploring that hillside and still not uncovered all it had to offer. It felt like walking through a living manuscript—one filled with stories too old or too holy to be bound by paper.

When I finally returned, dusty and awestruck, I was met by a vision that belonged in myth. A woman stood on the patio, her long blond hair pulled loosely to one side, her proportions so striking they might make Venus herself envious. She introduced herself as Tracy—Peterson’s girlfriend. But it wasn’t just her beauty that held presence; it was the grace with which she moved, the quiet intelligence in her eyes. There was something old-world about her, and yet thoroughly grounded.

She invited me to join her and Peterson for tea beneath the patio umbrella. Peterson had just brewed a fresh batch of chai—warm, spiced, and fragrant with cardamom. We settled into the kind of conversation that arrives only when all guards have been let down. We traded stories. Laughed. Fell into silences that didn’t need to be filled. There was an ease between us, as though we’d all known each other for years. But I imagine that’s part of Peterson’s gift: making people feel at home not just in his space, but in themselves.

In that golden late-afternoon light, time slowed. I was no longer a visitor—I was a witness to something sacred. A phase closing. Another beginning.

And yet, even in the richness of what he’s built, Peterson is looking forward.

His next chapter is already unfolding: travel once again, only this time as a guide, a grandfather, a living bridge between generations. He’s preparing to take his grandchildren across the globe—not just to show them the world, but to help them feel it. To teach them what it means to touch the thread of a Turkish rug and know its weight. To sleep beneath stars that have watched over temples and tents alike. To understand not just where we come from, but how to move forward with reverence.

There is something deeply moving about a man who has lived so fully—and still hungers for more. Not in a way that clings, but in a way that offers. To live a life as full as Peterson’s is to accept that the greatest act of legacy is not what you hold, but what you pass on.

This is what separates him in a world drowning in excess. Today, accumulation often means nothing more than clutter. But Conway of Asia is not clutter—it is a collection of spirit. A rare bastion of meaning in a market that has forgotten how to make room for memory.

Each item in the shop is available for purchase, yes—but that transaction is merely the beginning. With every altar piece or carved bowl, you are offered a story. A thread into the life of a nomad, a prince, a monk, or a matriarch. And should you linger long enough in the shop, or find yourself lucky enough to catch Peterson when he’s there, you might be told that story. Or better yet—you’ll be encouraged to seek your own.

Because in the end, Peterson’s life is not just about collecting stories. It’s about inspiring them.

The morning I met him, I was standing at a crossroads in my own life. Caught between paths, unsure where to step next. I didn’t know that the carved owl outside his shop would be a kind of messenger. I didn’t know that inside, waiting among centuries of global memory, was a man who would remind me that the story of one’s life is not written all at once—it is built, choice by choice, chapter by chapter.

And sometimes, when you’ve lived it with enough courage and care, that story becomes something worth passing on.

Postscript: For the Seekers

There are some stories too sacred to write down. I was given the great privilege of hearing many of Peterson’s tales firsthand—from Parisian summers and forbidden rooftops to jail cells, lost rugs, and moments of absolute transcendence. But they are his to tell. If you're lucky enough to meet him in person, perhaps over a carved table from Northern India or beside a towering sculpture from Java, you may be entrusted with one yourself.

And if not, look closer.

In a hand-wrought spoon. In a lion’s tooth strung onto bone. In the careful knot of a centuries-old prayer rug.

The story is already there.

You simply need to listen.

Comments